Israel's Independence Day fell this year

on 27 April. For his homework my nine-year-old son had to interview

me about my military past. Before giving out the assignment, his

teacher had invited the father of one of the children, an IDF

colonel, to give a talk in full military uniform. The children were

fascinated. Urged to ask questions, they mostly wanted to know

whether he was afraid, though they also asked if he had killed

Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, whose picture and the picture of his destroyed

wheelchair were quite a hit on Israeli TV. The colonel said it was

another unit, not his, 'but he deserved to die,' and he promised the

children that 'we don't kill unless there is a really good reason.'

He ended the talk by telling the children he hoped that they too

would one day have the chance to become senior officers in the IDF.

Our life worsens, poverty is spreading,

education and health services are deteriorating, the middle class is

shrinking, and we are ruled by a junta whose money and power have

increased to an extent people refuse to believe, even when they are

confronted with the figures. A 45-year-old colonel who retires from

the army gets a lump sum of close to two million dollars, in

addition to a lifetime pension and a second career, usually as an

executive of one of the huge corporations, or in arms dealing.

When the average Israeli wants to

explain these privileges, he points out that 'throughout his career

the colonel has been risking his life.' But that's been a myth for

at least two decades now. The colonel hasn't been risking his life

because there is no longer a serious enemy. There is only the

Palestinian desire to live as a free nation which in the form of the

terrorist campaign is represented as an existential threat to the

state of Israel. But it doesn't threaten the existence of Israel. It

never did, but it sure helps the military ride the wave of panic.

The real struggle in Israeli society

today is not between doves and hawks, but between the majority who

take for granted the IDF's image as the defender of our nation, with

or without biblical quotes, and the minority who no longer buy it.

If the army does something bad it is always an exception (harig,

in Hebrew). Those who believe that we are fighting for our lives

also believe that we do our best to be humane, and more or less

succeed. This fragile complex of axioms depends either on foolish

optimism ('soon everything will be resolved') or on images.

Arguments don't work anymore.

The most effective images are those

of dismembered bodies, screaming mothers and mourning fathers. But

that is exactly why the BBC World Service is considered 'hostile'

here. It isn't because of the Vanunu affair, but because of the

images it broadcasts of everyday suffering on the other side of the

road, a ten-minute drive from the safety of our homes, our

swimming-pools, our happy lives. Even CNN was considered hostile as

long as it 'misbehaved', bringing us pictures which contradicted the

basic image of our existence. Atrocities are always perpetrated

against us, and the more brutal Israel becomes, the more it depends

on our image as the eternal victim. Hence the importance of the

Holocaust since the end of the 1980s (the first intifada), and its

return into Hebrew literature (David Grossman's See under: Love).

The Holocaust is part of the victim imagery, hence the madness of

state-subsidised school trips to Auschwitz. This has less to do with

understanding the past than with reproducing an environment in which

we exist in the present tense as victims. Together with that comes

the imagery of the healthy, beautiful, sensitive soldiers.

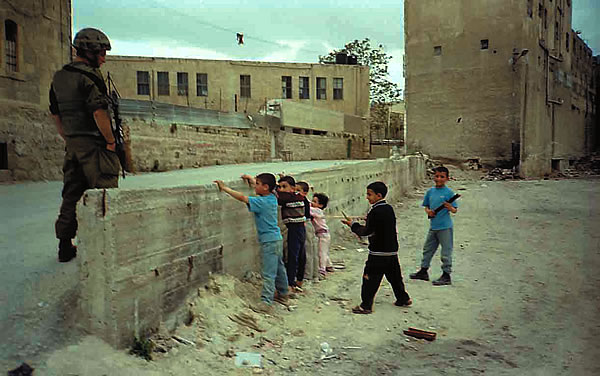

This is the context, at the

crossroads between the expanding (slowly, and maybe too little and

too late) refusenik movement and the ever growing despair, evident

at an exhibition called 'Breaking the Silence' ('Shovrim Shtika')

which opened in early June in Tel Aviv College: an exhibition of

photographs taken by mostly unnamed conscripts who served in Hebron.

(Their brigade commander was the colonel who gave the talk to my

son's class.) Sixty of the 90 photos record aspects of the conflict

between the Palestinians and the settlers, but 30 show the soldiers

at their daily routine - and the routine tells all. Indeed, towards

the end of June, the IDF's military police raided the exhibit,

'confiscating', as Haaretz put it, 'a folder containing

newspaper clips about the exhibit, as well as a videotape including

statements made by 70 soldiers about their experiences in Hebron'.

Four of the young men who organised the exhibition were called in

for interrogation. What were they interrogated about? Well, they are

suspected of having committed the crimes they documented on their

video - abusing Palestinians, destroying property etc.

Every once in a while opposition

arises from within the monster. Hence the Courage to Refuse

movement, the letter last September signed by 27 pilots who refused

to attack civilian populations in the Occupied Territories, the

letter in December from an elite commando unit that refused to

fight, and so on. A society living in the past as if it were the

present is vulnerable: the past/ present becomes a double-edged

sword. You may be sued if you call anybody here a 'Nazi', but one

hears it a lot. It would be more appropriate to compare Israeli

brutality with the French in Algeria, or the British in Sudan or

Malaysia, but we are taken up with the notion of 'our past turning

into our present'.

Moral repulsion isn't the only

factor, however. Young men who join the army want to fight in the

most sophisticated tanks, to fire the most frightening cannon, to

fly the brand new jet fighters, to operate the Apache helicopters,

to conquer the most heavily fortified enemy positions, to parachute

behind enemy lines. Then, after all their extremely difficult

training, after all the suffering and ambition, they find there is

no heroism, no glory, no diving as marine commandos under the waters

of the Persian Gulf. Instead, all they do is throw families out of

their homes in the middle of the night, demolish their houses, bomb

a six-storey building in Gaza, starve a town, harass women at

checkpoints, watch Shin Bet torture detainees, bring more misery to

the refugee camps.

What the Israeli army (like the

Israeli state) needs to reproduce in its soldiers is either sheer

racism - that is, faith in 'the murderous nature of the Arabs' - or

a brand of religious messianism, neo-Nazi ideology wrapped in

Judaism. One of the photographs in the exhibition shows a piece of

settler graffiti in Hebron which reads: 'Arabs to Gas Chambers'.

This kind of discourse has its weakness: it needs soldiers to fight

for it. There are a lot who won't.

Right now, the former soldiers who

took part in the exhibition - it closed at the beginning of the

month - are working on what they call journalistic research, though

it looks as if they are collecting evidence for some sort of

imaginary trial. The exception incriminates an individual soldier;

if you can show that it is the rule you incriminate the true

criminals of war, the heads of the IDF and the government. These

ex-soldiers are making contact with conscripts and reservists from

other brigades, gathering photos, confessions, testimonies for

further exhibitions. What they are telling us is common knowledge

beyond the hill, across the checkpoints, in every shattered

Palestinian kindergarten. They are doing it because they still

believe in some sort of Israeli justice. That faith, I fear, has no

basis in reality. On the other hand, how else can one become a

decent man, if not by believing in some sort of justice, in some

sort of place to come to terms with power? The Place is one of the

many names of God in Hebrew.

'First week, first time at the

checkpoint, at the passage between the Palestinian area and a street

where only Jews can go. Those guys have to stop, there's a line,

then they hand you their ID cards through the fence, you check them,

and let them through. This guy with me yells: "Waqif! Stop!"

The man didn't understand and took one more step. Then he yells

again, "Waqif!" and the man freezes. So the soldier decided

that because the guy took this one extra step he'll be detained. I

said to him: "Listen, what are you doing?" He said: "No, no, don't

argue, at least not in front of them. I'm not going to trust you

anymore, you're not reliable." Eventually one of the patrol

commanders came over, and I said: "What's the deal, how long do you

want to detain him for?" He said: "You can do whatever you want,

whatever you feel like doing. If you feel there's a problem with

what he's done, if you feel something's wrong, even the slightest

thing, you can detain him for as long as you want." And then I got

it, a man who's been in Hebron a week, it has nothing to do with

rank, he can do whatever he wants. There are no rules, everything is

permissible.'

'Another thing I remember from Hebron

is the so-called "grass widow" procedure - the name for a house the

army takes over and turns into an observation post, the home of a

Palestinian family, not a family of terrorists, just a family whose

home made a good observation post. You're in somebody's house, and

everything is littered with shit, there are cartridges and glass on

the stairs, so you can hear if anyone is approaching. It's a house

covered in camouflage netting so people can't see what you're doing

inside. You find yourself in a Palestinian neighbourhood, in some

family's home, and it's totally surreal, because there you are,

sitting in the living-room, listening for people coming to attack

you. There was food left behind, and there was a TV, but we weren't

allowed to turn it on - to use their electricity, this would be too

much, this would be considered "bad occupation".'

'It was Friday night, and the

auxiliary company, which was stationed with us in Harsina,

eliminated two terrorists. Friday night dinner was, of course, a

very happy affair, and the whole base was jumping. As I was leaving

dinner, an armoured ambulance arrived with the terrorists' corpses,

and the two terrorists' corpses were held up in a standing position

by three people who were posing for photographs. Even I was shocked

by this sight, I closed my eyes so as not to see and walked away. I

really didn't feel like looking at terrorists' corpses.'

'Our job was to stop the Palestinians

at the checkpoint and tell them they can't pass this way any more.

Maybe a month ago they could, but now they can't. On the other hand

there were all these old ladies who had to pass to get to their

homes, so we'd point in the direction of the opening through which

they could go without us noticing. It was an absurd situation. Our

officers also knew about this opening. They told us about it. Nobody

really cared about it. It made us wonder what we were doing at the

checkpoint. Why was it forbidden to pass? It was really a form of

collective punishment. You're not allowed to pass because you're not

allowed to pass. If you want to commit a terrorist attack, turn

right there and then left.'

'I was ashamed of myself the day I

realised that I simply enjoy the feeling of power. Not merely enjoy

it, need it. And then, when someone suddenly says no to you, you

say: what do you mean no? Where do you get the chutzpah from to say

no to me? Forget for a moment that I think that all those Jews are

mad, and I actually want peace and believe we should leave the

Territories, how dare you say no to me? I am the Law! I am the Law

here! Once I was at a checkpoint, a temporary one, a so-called

strangulation checkpoint blocking the entrance to a village. On one

side a line of cars wanting to get out, and on the other side a line

of cars wanting to get in, a huge line, and suddenly you have a

mighty force at the tip of your fingers. I stand there, pointing at

someone, gesturing to you to do this or that, and you do this or

that, the car starts, moves towards me, halts beside me. The next

car follows, you signal, it stops. You start playing with them, like

a computer game. You come here, you go there, like this. You barely

move, you make them obey the tip of your finger. It's a mighty

feeling.'

'On patrol in Abu Sneina we make a

check post where you stop cars and check them out. We stop a guy we

know, who always hangs around, doesn't make trouble. Connections are

made, even if we don't speak the same language and even if it's hard

to explain. The commander stops him. "You cover the front. You cover

the back." So I cover the front. The commander says to him: "Go on,

get going. Get out your jack." The guy just stands there and stares.

He doesn't understand what they want. So the commander yells at him

that he should get out his jack and begin to take the wheels off.

I'm standing near a stone wall and the guy comes over and takes a

stone to put under the car, and then another stone. At that point,

the commander comes over to me and says: "Does this look humane to

you?" He has a horrible grin on his face. It's awful. I can't do

anything. I don't have enough air to say anything. I take my helmet

off and lean on the stone wall, still covering the front, and I

cry.'

'Once a little kid, a boy of about

six, passed by me at my post. He said to me: "Soldier, listen, don't

get annoyed, don't try and stop me, I'm going out to kill some

Arabs." I look at the kid and don't quite understand exactly what

I'm supposed to do. So he says: "First, I'm going to buy a popsicle

at Gotnik's" - that's their grocery store - "then I'm going to kill

some Arabs." I had nothing to say to him. Nothing. I went completely

blank. And that's not such a simple thing, that a city, that such an

experience can silence someone who was an educator, a counsellor,

who believed in education, who believed in talking to people, even

if their opinions were different. But I had nothing to say to a kid

like that. There's nothing to say to him.'

'The very existence of the checkpoint

is humiliating. I guard, or enable the existence of, 500 Jewish

settlers at the expense of 15,000 people under direct occupation in

the H2 area and another 140,000-160,000 in the surrounding areas of

Hebron. It makes no difference how pleasant I am to them. I will

still be their enemy. As long as you want to keep these 500 people

in Hebron alive and enable them to go about their existence in a

reasonable manner, you have to destroy the reasonable existence of

all the rest. There's no alternative. For the most part, these are

real security considerations. They're not imaginary. If you want to

protect the settlers from being shot at from above, you have to

occupy all the hills around them. There are people living on those

hills. They have to be subdued, they have to be detained, they have

to be hurt at times. But as long as the government has decided that

the settlement in Hebron will remain intact, the cruelty is there,

and it doesn't matter whether or not we act nice.'

'Whenever we feel like it, we choose

a house on the map, we go on in. "Jaysh, jaysh, iftah al bab" -

"army, army, open the door" - and they open the door. We move all

the men into one room, all the women into another, and place them

under guard. The rest of the unit does whatever they please, except

destroy equipment - it goes without saying - and there's no helping

yourself to anything: we have to cause as little harm to the people

as possible, as little physical damage as possible. If I try to

imagine the reverse situation: if they had entered my home, not a

police force with a warrant, but a unit of soldiers, if they had

burst into my home, shoved my mother and little sister into my

bedroom, and forced my father and my younger brother and me into the

living-room, pointing their guns at us, laughing, smiling, and we

didn't always understand what the soldiers were saying while they

emptied the drawers and searched through the things. Oops it fell,

broken - all kinds of photos, of my grandmother and grandfather, all

kinds of sentimental things that you wouldn't want anyone else to

see. There is no justification for this. If there is a suspicion

that a terrorist has entered a house, so be it. But just to enter a

home, any home: here I've chosen one, look what fun. We go in, we

check it out, we cause a bit of injustice, we've asserted our

military presence and then we move on.'

'There's a very clear and powerful

connection between how much time you serve in the Territories and

how fucked in the head you get. If someone is in the Territories

half a year, he's a beginner, they don't allow him into the

interesting places, he does guard-duty, all he does is just grow

more and more bitter, angry. The more shit he eats, from the Jews

and the Arabs and the army and the state, they call that numbness

but I don't, because serving in the Territories isn't about

numbness, it's a high, a sort of negative high: you're always tired,

you're always hungry, you always have to go to the bathroom, you're

always scared to die, you're always eager to catch that terrorist.

It's a life without rest. Even when you sleep, you don't sleep well.

I don't remember even once sleeping well in Hebron. It's simply an

experience that no human being should have. It fucks with your head.

It's the experience of a hunted animal, a hunting animal, of an

animal, whatever.'

'When I served in Hebron, for the

first time in my life I felt different about being a Jew. I can't

explain it. But the Tomb of the Patriarchs, the ancestral city, it

did something to me. I don't know if I was defending the State of

Israel, but I was defending Jews who were part of the state, and in

a city where the controversy is different from other Arab cities. It

was the worshippers' route. One day, out of the blue, a group of

about six Jewish women with six or seven little girls simply started

running around, started kicking stalls and turning them over, and

spitting on Arabs and elderly people. One of the women picked up a

rock and shattered the window of a barber shop. A man comes out, and

I find myself, on the one hand, trying to take the rock away from

her, and on the other hand, defending her, so that they won't beat

the shit out of her. So on the one hand you say to yourself, fuck

it, I'm supposed to guard the Jews that are here. But these Jews

don't behave with the same morality or values I was raised on. If

they're capable of writing on the Arabs' doors "Arabs Out" or "Death

to the Arabs," and drawing a Star of David, which to me is like a

swastika when they draw it like that, then somehow the term "Jew"

has changed a little for me.'

'Once I was in Hebron, when from a

gate near our post that leads to the Kasbah, and from which it is

forbidden to enter or exit, came a man in his fifties or sixties

with a few women and small children. You walk up to him and say in

Arabic: "Stop, there's a curfew, go home." And then he starts to

argue with you. And he gets bold, like he believes that he'll get

through in the end. He's not trying to weasel his way through, he

really believes that he's in the right. And that confuses you. You

remember that actually you would like to let him pass, but you're

not supposed to let him pass, and how dare he stand there in front

of you . . . Finally the patrol shows up, and from an argument

between two soldiers and ten people, it becomes an argument between

ten soldiers and ten people, with an officer who, naturally, is less

inclined to restrain himself. Weapons are cocked, aimed, not

straight at him, but at his legs. "Get the hell out of here, enough

talk!" I was standing closest to him, about a metre or two. He was

all dressed up, wearing a suit and a kaffiyeh, he looked really

respectable. And I was standing there with my weapon, close to my

chest, trying to defend myself, protect myself. I was afraid that he

was going to try something. And the atmosphere was charged, more

than usual. Then he sticks out his chest, and both his fists are

tightly closed. My finger moves to the safety catch, and then I see

his eyes are filled with tears, and he says something in Arabic,

turns around, and goes. And his clan follows him. I'm not exactly

sure why this incident is engraved in my memory out of all the times

I told people to scram when there was a curfew, but there was

something so noble about him, and I felt like the scum of the earth.

Like, what am I doing here?'

'That morning, a fairly big group

arrived in Hebron, around 15 Jews from France. They were all

religious Jews. They were in a good mood, really having a great

time, and I spent my entire shift following this gang of Jews around

and trying to keep them from destroying the town. They just wandered

around, picked up every stone they saw, and started throwing them in

Arabs' windows, and overturning whatever they came across. There's

no horror story here: they didn't catch some Arab and kill him or

anything like that, but what bothered me is that maybe someone told

them that there's a place in the world where a Jew can take all of

his rage out on Arab people, and simply do anything. Come to a

Palestinian town, and do whatever he wants, and the soldiers will

always be there to back him up. Because that was my job, to protect

them and make sure that nothing happened to them.'

Yitzhak Laor is a novelist and edits the Hebrew

quarterly Mita’am.